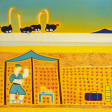

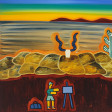

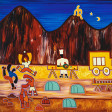

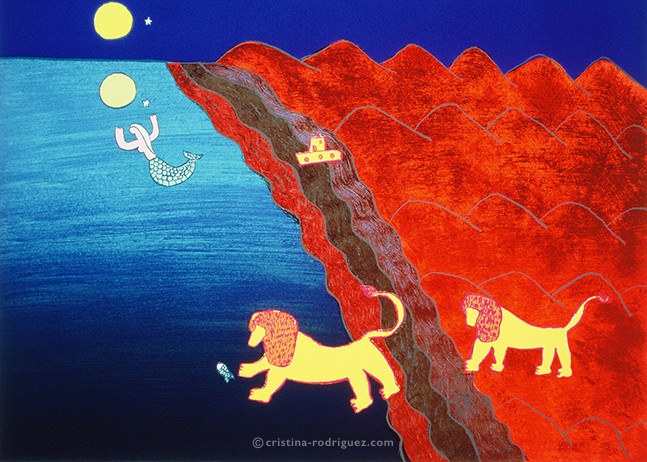

The Desert Is not Deserted

The Orangery Gallery

Holland Park

London, UK

2004

© Cristina Rodriguez

Ref: CR03-12A

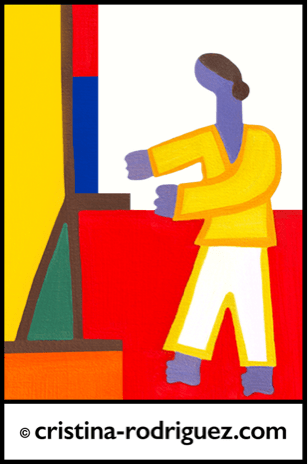

Title:

The Story That the Travel Writer Told Me

Year: 2003

Medium: Screenprint edition of 75

Size: 55 x 76 cm

“This exhibition was inspired by my ten-day trek through the Namib-Naukluft Park in Namibia. Every day, I encountered plants that were ten million years old and survived from the mist that came from the sea, flowers with the most astonishing colours, born out of the sand, trees that sheltered themselves inside caves, small and large extraordinary animals. I was astonished each of those ten days, I was astonished while I was doing the paintings, I’m still astonished by the marvel of the desert and how undeserted it is.”