The Desert Is not Deserted

'Travel is never just a journey to another physical place - it's always an inner journey, too.'

Think of the word 'desert' - what does it bring to mind ? For many of us, the desert seems an unsettling, disturbing place - too hot, too cold, at once hard to grasp and yet all-engulfing. We are fascinated by its alien quality, its other-worldliness - yet also frightened. We imagine that this sun-swept landscape must be an empty place, bleak and barren. We might end up alone with ourselves there. Perhaps, indeed, that is what both terrifies and intrigues us most.

In June 2002, Cristina Rodriguez left her West London studio to take part in an ten-day trek through the Namibian Desert. The expedition was organised to raise funds for the Mines Advisory Group (MAG), a Nobel Prize-winning charity that works to clear mines and unexploded ordnance all around the world. The trek began at the entrance to the Namib-Naukluft Park near Karib in central Namibia. It concluded, many miles later, within sight of the western coast of Southern Africa.

In between these two points stretch some of the harshest yet most extraordinary environments on earth. The journey was an experience that tested not only the physical and spiritual strength of the participants, but also pushed at the limits of their imaginations. Apparently endless flat plains of gravel terminate in sudden rocky outcrops or jagged mountains, punctuated along the way with valleys and hidden oases, all washed over by ever-changing effects of sunlight and shadow. Life has evolved there, over hundreds of thousands of years, so that it dances in time with such extreme conditions. The Namibian Desert is an absolutely vast place, where the scenery may change from minute to minute yet where everything looks like something out of a dream, and where the miniscule can surprise as intensely as the monumental. As the artist herself puts it,

'I spent hours looking at those changing, impossibly beautiful skies, the colours of the sand, those unreal flowers growing up in the middle of nowhere. We never saw lions, giraffes, elephants; we saw humble animals - a tiny chameleon, a few ostriches, a zebra, scary baboons and a beautiful gazelle.'

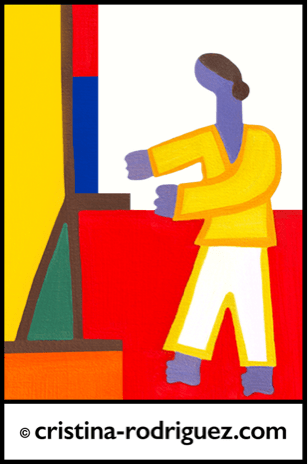

Rodriguez's new exhibition, The Desert Is not Deserted, comes directly out of her Namibian experience. Comprising eleven major new paintings and a limited-edition screenprint, it is Rodriguez's way of leading the viewer along with her on this desert journey - the inner journey, as well as the literal physical one. Brilliant surprising colour, lyrical compositions and a lively sense of curiosity lead the way. As ever, in Rodriguez's work, part of the excitement lies in watching the artist's symbolic vocabulary expand and evolve in order to expose the reality that lies beneath the surface of things - to distil the fantastic from the apparently mundane and wrap it all up in the poetry of pure magic.

Enchantment overlaps sympathy, curiosity and more than a little humour. The journey begins with The Arrival and Joe - a beginners' guide to the desert, where the handsome guide and welcoming cold drink can't quite distract us from the hallucinogenic strangeness of the ostriches, the pathos of the departing bus cutting off our last links with civilisation, or - most powerfully - the radiant, distant, infinitely vast horizon stretching out before us. In The Scene That Never Happened, Joe joins a zebra in a sunset pas-de-deux played out against a backdrop of ardent rose-red and tangerine. It's as if these two graceful creatures of the desert share a magical life that the visitor, for now at least, can only watch with wonder.

But then it is time to leave the safety of the campsite and to set off into terra incognita. Here, Rodriguez's brushwork encodes whole new levels of texture and incident in order to convey the variety of sensations produced by the ever-changing landscape. The colour contrasts, never less than intense, become objects of wonder in their own right. Compositions veer between the literally real and geometrically intoxicating, as if teasing us to draw the line between reality and dream. Yet this is a landscape so unfamiliar to us that such certainties have to be discarded from the baggage we carry with us. A work like The Quiver Tree in the Cave Surrounded by the Most Beautiful Sunset, with its vertiginous hills and emblematic figures, has a mythic quality which seems more evocative of actual memory than any photograph could possibly be. Desert life - the chameleon in The Girl With the Fabulous Legs Looking for the Chameleon, the snake in The Girl With the Feather Crossing the Mountain, the strange plant in The Shadows of the Artist and the Journalist Reaching the Gazelle - takes on a totemic quality. Things are literally seen in a whole new light here - the intense, slightly unearthly light of the desert itself.

After so much incident - mountains climbed, plains crossed, horizons endlessly pursued - the journey draws to a close with At Last, the First Signs of Civilization. Here we are reminded that our fellow human beings, too, make their homes in this strange and forbidding-looking landscape - something underscored by the colour here, so that the Namibians seem to fit in with the land - to rhyme with it chromatically - while the visitors still stand out. Perhaps, then, we - not the desert - are alien? Finally, in The Last Night in the Campsite Being Visited by the Moon, Rodriguez and her companions spend their last evening together, celebrating the challenges they have faced and the bonds they have forged. It's a euphorically happy scene, playful and bright, but the dark presence of the mountains, surmounted by the emblematic moon figure, balance this with a note of the eternal - a reminder that the moon's cycles, like the desert itself, will continue long after the footprints of this particular journey have been swept away.

The screenprint which closes the exhibition takes the magic a step further. Inspired by a tale told to Rodriguez by the travel writer , it depicts a moment both exotic and convincing, in the way that a vivid dream sometimes seems more true than waking life - the moonlit moment when lions come down from the plains to fish on the shores of Namibia's infamous Skeleton Coast, watched over by a reflective mermaid. The colours here - not least, the refulgently brilliant blues - are every bit as marvellous and strange as the story they convey. Like the best sort of fairy-tale, this is an image that lodges in the mind and won't let go. Is this, we wonder, what happens all around us when no one is looking? Can we be sure - really sure - that it isn't?

The Desert Is not Deserted is full of bright, lively, vibrant paintings. The overriding sensation is one of amazement and delight at the strangeness and beauty of the world around us. But although there is sometimes something childlike about the drawing - the simplified human forms, the strong local colour - Rodriguez is by no means a naive painter. Rather, these works have developed as a way of expressing a profound and personal vision. As Rodriguez puts it,

'I was drawn inwards, in complete silence, in awe of that ancient environment, which is always changing, never still. And there were, of course, my fellow travellers, each intent of raising much needed funds for MAG, from whom I learnt a great amount and to whom this exhibition is dedicated. All of us were transformed by our experience and I want to offer them an extension of that experience - my own interpretation of the trek.'

Rodriguez's interpretation of her time in the desert is richly infused with wonder, awe, humour and enchantment. Yet these paintings are about more than a single place or a single time. Rather, at some more profound level, they have something to say about the nature of journeys themselves. To return to the lines that began this essay, Rodriguez is not just talking about the world around us, but rather about the way in which we see it - the awakening of our capacity to recognize the miraculous that happens all around us, every day. This is a message as relevant, and as inspiring, in London as it is in Southern Africa. Nothing in our world is deserted, nothing without its own capacity for revelation, if we open our eyes to see it.

Bunny Smedley

Art critic

2004