Jump Into Reality

"MIRACLES ARE IN THE AIR". Artist Cristina Rodriguez is talking me through her forthcoming show, Jump Into Reality. The theme is motherhood, and the painting she is showing me, Happy Birthday to You, is a wildly colourful, almost riotous evocation of a child's birthday party. There's a clown, and there's a tremendous air of celebration, of private joy shared with a community of family and friends. It is one of the show's key images. "Every single culture celebrates the birthday", she explains. "It's a celebration of a new life - of a miracle."

The miracle of motherhood is one that Rodriguez has experienced firsthand. Her own son, Lucas, was born two years ago. As a painter, her work has frequently drawn attention to the strangeness of the everyday world - to the marvellous side of the ordinary that we are all too quick to take for granted. Hence Rodriguez's decision to distil parenthood into art. The result is Jump Into Reality, a series of powerful new paintings about the creation of a new life.

Rodriguez is alert to the way in which central human experiences transcend geographical boundaries. Born in Colombia, she studied at the University of Los Andes in Bogota, holding her first show there in 1987. In I989 she left for London, where in 1991 she received an MA from the Slade School of Fine Arts. She has also spent time painting in Zimbabwe and New York. Although she now lives in London, she speaks passionately of Colombia - of the poverty and the violence, but also of the intense cultural richness of the country that produced Gabriel Garcia Marquez and gave birth to 'magic realism'.

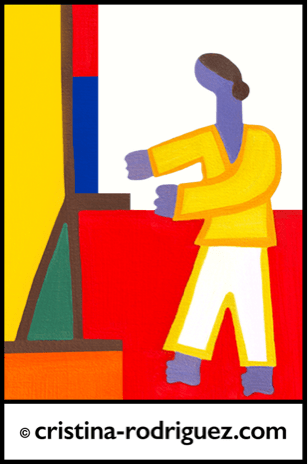

Rodriguez's South American heritage remains a powerful influence on her work. It is there in her confident use of bright oil colours - violet brushed over ultramarine, or ardent Indian yellow cooled down here and there with passages of grey or black. It is also evident in her skill at condensing complex reality into her own symbolic language, and perhaps even in her robust adherence to figurative, narrative painting, regardless of whether it's in or out of fashion. From the beginning, Rodriguez planned Jump Into Reality to follow the narrative structure of a conception, birth and infancy; she painted the works in the order in which they appear in the show.

Yet there's nothing remotely naïve here. Stepping into Rodriguez's north London studio, I encounter the complex web of associations that informs her work. There, alongside the neatly piled tubes of oil colours, are monographs on Henry Moore and Frida Kahlo, pre-Colombian art and Picasso. On the walls are old family photos, playfully romantic notes from her husband Charles Marsden-Smedley, photographs of her adorable son Lucas. There are shells, 'found' images, a Moussorgsky album. "I believe in the muse, but you have to work for her to be there with you," she says, a little ruefully. In conversation, Rodriguez cites films and books, speaks of a composition in terms of pauses and crescendos, and admits that until the moment she starts work on a painting, she never knows how all the diverse elements will combine themselves - only that she knows when she gets it right.

Like all of us, her experience of motherhood is at once personal and cultural. Everyone has a mother, everyone's been a baby; parenthood is a theme which, in one form or another, has always been omnipresent in art and literature. Hence it is fitting that some of the works in the show focus on the archetypal aspects of birth. The Man, the Woman, the Tree is a monochrome work which shows exactly that - "these are two separate realities united in planting a seed," explains Rodriguez - while a diptych titled The Meals traces the transition from the timeless ritual of breastfeeding through to the highly acculturated world of the tea-party, in which toddlers imitate the grown-ups and prepare to take their place in the wider social world.

Many of the images are intensely specific, recalling moments of great significance to Rodriguez. The Nursery depicts a series of childhood toys - little objects of almost infinite value. "When you have a child," explains Rodriguez, "you recognise the importance of a plastic duck - if the duck disappears, it's a major disaster in a home". There are delightful evocations of holidays, such as the luminous The Picnic in the Highlands.

Meanwhile, Four Moments in One Morning recalls the unforgettable moment when a baby takes his first steps, watched over by his father. At one level, it's an impeccably skillful composition. Shifting horizon-lines mean that at one moment we're with the father, looking down at the baby, while in the next we're down near the floor, observing life from a baby's-eye-view. The red flower that blossoms in each of the four panels remains unchanged, bearing witness to the speed of transition from crawling infant to fully ambulatory, autonomous personhood. But there's more than mere skill here. "This series gives me so much tenderness" says Rodriguez, her face softening as she turns towards the canvases depicting husband and son; looking at her, you know she means it.

London is also there, very evidently, in Jump into Reality. One series of panels which revolves around play - The Pond, The Playground and Lunchtime - is full of literal detail borrowed from Ravenscourt Park, where Rodriguez has spent many happy hours with her son. The pond with the tree in the middle, the above-ground Tube line, the frozen hands of the cupola clock these are talismanic details transcribed from real life in a particular place, although the general sense of movement and fresh-air high spirits will be recognisable to anyone. Likewise, Supermarket With a View takes what one might assume was a fairly prosaic reality - the Ladbroke Grove Sainsburys - and finds wonder in the displays of food, the nearby canal, the floating domesticity of the canal barges. If you've never been there, it's still a delightful picture, but for those of you who know the place well, it's pure enchantment.

And this is the key to the distinctive nature of Rodriguez's work - a happy and fruitful marriage between the specific and the universal, held together with the odd miracle. "I think the more personal things are, the more universal they are," she says, and her paintings reflect this. They evoke a world where the marvellous is an everyday occurrence - a world where mermaids and centaurs seem no more (and no less) magical than ducks and squirrels, where a north London supermarket radiates the glamorous exoticism of a story-book kingdom, and where the experience of giving birth transforms everything. It is, in other words, everyday reality as we know it - but shot through with glimmering stands of pure magic.

Bunny Smedley

Art critic

2001