The Desert Is not Deserted

Cristina Rodriguez's paintings of her journey in the Namibian desert perfectly distil one of the truths about travel in remote places - that what we take from such journeys is, above all, a series of moments. We might be suffering severe discomfort - wilting from heat or laid low by some grumbling ailment; we might be troubled by a mysterious rash; we might be anxious at dusk, about wild animals or the zealous members of some vicious local freedom movement; we might be weak with thirst, heavy-limbed with exertion; in short, it might all be going very badly indeed. But then comes the glimpse of a distant horizon, a tiny botanic miracle, a soaring raptor, a character or figure revealed in all its comedy and grace - and we are suddenly catapaulted to joy, to a re-affirmation of the world's wonders.

Only the best activities offer such mercurial rewards, but it is notoriously difficult to capture them - either in print or on canvas. Cristina Rodriguez is ideally suited to the role of travelling painter. Born in Colombia, she spent a childhood on the move - with spells in Peru, Germany and Zimbabwe. She has lived in the UK on and off for fifteen years. She has visited most of Europe's more colourful corners, and many beyond. In her work she sustains that essential artist's attribute - the eye of a stranger.

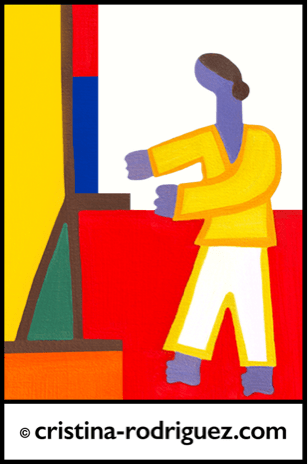

Yet many of her perceptions are also consistent with her native Colombia - the rich colours, the flamboyant figures, the exuberance of the composition - and the narrative. Colombia is a place where narrative is all. That very human tendency, to make mythologies from the randomness of our lives, is in Colombia an art form in itself. Tales are woven out of the most commonplace events. We have only to look at the titles of these works to realise that each one is a little story - The Girl With the Fabulous Legs Looking for the Chameleon, The Reward After the Hazardous Climb, The Quiver Tree in the Cave Surrounded by the Most Beautiful Sunset, The Girl With the Feather Crossing the Mountain, The Scene That Never Happened.

I have always had a horror of aimless travel. When in my early twenties I first began to roam beyond western Europe, I became acutely aware of how easy it would be to become lost, to spend years drifting from place to place. Travel is a perilous freedom. The pleasures of footloose wandering are also its greatest pitfall: you can go anywhere, do anything, learn everything - but without some sort of shape, some narrative, it is meaningless. The best journeys to my mind are those that flirt with these dangers, that pitch the traveller into the wilderness but which then magically take on some revelatory shape.

Likewise an unexamined journey is not worth making. Ruskin urged us all to draw - not because we might be any good, but to improve our ability to see. Drawing a scene reveals it. The ease and speed with which we now travel means that we run the risk of seeing so much that we end up noticing nothing. Cristina's pictures urge us to take our time, to notice the details. Hers are scenes that appear reduced to their essential features, rinsed of detail. They give us the sense of space, the simplicity of each moment. But they also celebrate details, the flowers in one corner, the figures playing and exercising, the line of glasses on a table, the glowing half-moons of the cattle horns.

The art of travel is no different from the art of art. To do it well requires the same intensity of awareness, the same abstraction, the same discovery of order in chaotic images and events. It means forgetting about the stone in our shoe, the heat of midday, the fear at dusk. It means banishing our selves in order to become immersed in the wide world. The success of Cristina Rodriguez's The Desert Is not Deserted is that it encourages us to do precisely that.

Phillip Marsden

Writer

2004